Music Notation and Music Education - Part 1

The relationship between music notation

and the development of an effective system of music education has

been clear since the earliest forms of written notation.

Systems of notation in many cultures developed as a teaching aids rather than instructions to performers. In medieval Europe the development of notation had close educational links, revealed by the work of Guido of Arezzo in the eleventh century. Guido furthered the study of musical theory and notation in Micrologus (ca. 1025-28), which drew on theoretical studies of the ninth Century, Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, and from early Greek theory. Guidos’ developments were of a particularly practical nature, music being an important part of monastic education at the timei. Notation was primarily used to help singing students to learn and remember lines of melody. The ability to have these songs in written form would soon lead to more complex forms of polyphonic music, where musicians would sing independent parts as appose to the traditional unison singing of the early medieval period. By the end of the eleventh century, notation had developed that allowed for the consistent repetitions of musical works, which contained separate parts.

With the evolution of notation, and the production of theoretical music books like the Musica enchiriadis, came the means to create ever more complex musical compositions. Advances in rhythmic notation gave composers like Leonin and Perotin opportunities to innovate, creating new forms and structures. Their work in the early Thirteenth Century developed ideas of harmony and counterpoint, which lead to ever more radical innovations in music composition. Notation would develop to give composers more control over every musical parameter. As a result the use and interpretation of notation became more and more specialised for both the composer and the performer.

Systems of notation in many cultures developed as a teaching aids rather than instructions to performers. In medieval Europe the development of notation had close educational links, revealed by the work of Guido of Arezzo in the eleventh century. Guido furthered the study of musical theory and notation in Micrologus (ca. 1025-28), which drew on theoretical studies of the ninth Century, Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, and from early Greek theory. Guidos’ developments were of a particularly practical nature, music being an important part of monastic education at the timei. Notation was primarily used to help singing students to learn and remember lines of melody. The ability to have these songs in written form would soon lead to more complex forms of polyphonic music, where musicians would sing independent parts as appose to the traditional unison singing of the early medieval period. By the end of the eleventh century, notation had developed that allowed for the consistent repetitions of musical works, which contained separate parts.

With the evolution of notation, and the production of theoretical music books like the Musica enchiriadis, came the means to create ever more complex musical compositions. Advances in rhythmic notation gave composers like Leonin and Perotin opportunities to innovate, creating new forms and structures. Their work in the early Thirteenth Century developed ideas of harmony and counterpoint, which lead to ever more radical innovations in music composition. Notation would develop to give composers more control over every musical parameter. As a result the use and interpretation of notation became more and more specialised for both the composer and the performer.

As composers became more

adventurous in their composition and performers became more virtuosic

in their technique, the division grew until specialized study was

required in each area. As the development of notation created a clear

division between composer and performer, it created an even larger

division between those involved in creating music and those who

consumed it. This distinction between 'musician' and 'non-musician',

creator and consumer, is one that is still part of western musical

culture and one that had a negative effect on music education since

the introduction of systems of mass education in the mid to late 19th

century. Although traditional notation is essential in the context of

a specialised music school, it falls short in practical terms when

used to teach introductory music to classes of mixed ability and

musical experience.

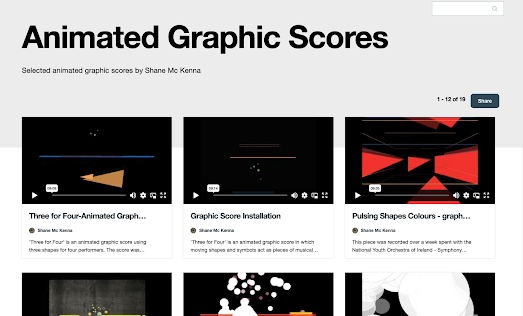

Reform in musical notation

in the 1950's lead to many changes, both in the music itself and in

the way it was being created. Graphic notation suggested a different

relationship between the composer and the performer. Indeterminate

notation systems would take control away from the composer and allow

the musician more creative input. The interpretive and sometimes

improvisatory role of the musician questioned the traditional ideas

of musicianship and musicality. It also represented a search for

alternatives to conventional harmony and traditional instrumentation.

New notation was often used to create a collaborative relationship

where the lines between composer and performer were blurred.

Composers like John Cage, Cornelius Cardew and Earle Browne were

relinquishing control over every detail of their composition and

trusting the interpretation of the performer.

For some composers this

opened up the idea of democratisation of music. Graphic notation

could allow composer to created pieces that anyone was free to

interpret, regardless of their musical background or level of

experience. It was this important change in attitude towards notation

and musicianship that lead music educationalists of the 60's and 70's

like Bernard Rands and George Self to experiment with new ways to

explore music without using traditional musical notation. This new

notation would allow them to explore, not only the basic concepts and

building blocks of music, but also the new world of contemporary

musical ideas.

The Need For New Notation in Music

Education

“Music is

an indispensable part of the child-centered curriculum as one of the

range of intelligences and as a special way of knowing an

learning”[2]

Although

conventional notation became the standard in formal music education

across the western world we must also consider the many forms of

music education that do not rely heavily on musical notation. Many

forms of folk music, including Irish music, still focus on the aural

tradition; passing down songs without written notation. This form of

education relies heavily on careful listening, repetition and

ensemble playing. It involves a completely different dynamic from

formal training. The importance of playing with others and learning

through participation, blurs the lines between teacher and student.

Here, playing and learning are one and the same. Another obvious

difference with western music education is that the composer of the

music is often unknown or of little importance to the performance or

study of the music. Combinations of anthropology and musicology have

given great insights into the importance of music in different and

varied societies around the world. In an examination of our own music

education system and our wider musical society, it is worth looking

to other cultures for comparisons. The work of John Blacking is of

particular relevance, as much of his research relates specifically to

the theory and practice of music education. After many years spent

studying the music of the Venda of South Africa, Blacking embarked on

a series of lectures, throughout the United Kingdom and United States

of America, which were specifically aimed at music educators. Three

themes were consistent in these lectures:

- The crucial aim of developing the musical capabilities of all children, rather than a select group of children.

- The uniquely transcendental or transformative properties of music, including its aesthetic, emotional and spiritual qualities, which thus justify its imperative as a curriculum subject.

- The critical need for music teachers to direct their efforts towards artistic-musical rather than non-musical ends.[2]

Blacking

talked of a society where music played a vital and functional role in

creating a sense of community and of individual worth and belonging.

From early childhood music is shared as a integral part of everyday

life, not as a specialist subject taught in a formal setting. Part of

the problem with music education in our primary level schools is the

perception that music is a subject that cannot be attempted by a

teacher without special training or vast musical experience. While

most teachers will happily take an art class without having formal

training in the use of watercolors, it is considered a more daunting

task to teach a music class. This is a kind of musical inferiority

complex that has been perpetuated through hundreds of years of

composers, musicians, critics and scholars, working under the premise

that music is at its most vital as a high art, presented by great

artists. This paper will present an alternative view, that musical

creation is too important to be left to a small minority and simply

listened to by the vast majority . The true value in music is to be

experienced by taking part.

Compose, Perform and Listen

One of the most valued concepts in music education today is that every lesson should involve the active participation of the class, where the students ‘learn by doing’. Students should have experience in the three key areas of performing, listening and composing, as part of every class. These are known as the three streams of music education. Each stream is considered of equal importance in leading to a full understanding of any given musical concept, giving the student opportunities to grow their knowledge in a range of ways.In a primary level class, the use of conventional notation to achieve each of these activities is difficult to say the least. Listening, with reference to a score, and performance may be achievable, but often the composition part is a step too far. Alternative notation can be used more effectively to deal with each of the three streams equally, while exploring the basic musical concepts that apply across different styles and genres of music. Many of the processes and musical ideas associated with traditional vocal and instrumental music can be explored through a more contemporary approach to music. Thomas A. Regelski chairman of the music education division of the School of Music, State University College, Fredonia, New York has written extensively on the subject, which he calls sound composition or soundscape. He advises the use of more contemporary ideas in music education:

“Because sound compositions involve composing,

performing and listening they are among the most efficient and

effective of all instructional tools” [3]

What's the solution? stay tuned for part 2 - The creation of a new notation for everyone!